THE SODOMIZED BOY

What he remembers is not the shock of pain

but waves of breath lifting and carrying him to the hollows of a cedar tree

where owls cover him with their wings.

He knows now the burgled house unlocks its own doors.

The murdered man solicits his death and pays the killer in advance.

The widower sleeping on his wife’s side of the bed is found naked

by moonlight.

Everything is a succession of Being, always busy becoming

something else.

A glass of water becomes the Pope, drop by drop.

The boy remembers this and is comforted.

.

CAROL AND I AT EVENING BY THE WHITE SALMON RIVER

Inside these diamond backed shadows, you are with me

as I am with the river.

Twenty-seven years married, now the night is coming.

The sky is a blue man in a sequin suit

falling down on blue knees by the river.

Under scrub oak trees all the mossy backed chickadees are feasting without a care,

turning over leaves shaped like hands that close

around each other as they dry.

.

I AM SATISFIED

“There is a love that will break ribs getting to your heart.”

one

You harnessed my anger, made me plow in a field of bones.

Taught me not to hear the world’s infected promises

not put my lips too near a dead thing’s mouth

but to kneel

and from my distance, look into the world’s yellow eyes.

See through them there is a light in outer darkness, that does not

look away.

Now I stand in front of waterfalls, gutted, reborn in water.

I am here in all this beauty and I am satisfied

with that.

two

Next moment I am crying. The whole creation is crying.

Pain is not an unwanted child standing in line for her own abortion.

Pain is the expected one we wait for all our lives.

To mend the heart

the surgeon’s knife cuts through walls of bone and muscle

and we are satisfied with that.

three

We meet on the river road and know each other by our masks.

When a man has nothing left to say, the ghost in him takes over.

The ghost speaks through the hole in the mask, as if it is alive.

The ghost says

“The blind running with coyotes through fir trees can clearly see

what those with eyes cannot.

The deaf play on blue guitars and sing

while those born with ears and a tongue are forever dumb.

All night long the cricket patiently rubs his legs together!

The living die and the dead dance in circles, dressed in feathers of a fish hawk.”

I say

there is a ghost in me who suffers and enjoys

and I am satisfied with that.

four

In the end we are like salmon

forced by our blood back to the spawning pool.

We are Chinook and Coho

cut by volcanic rock in narrow beds of white water streaming blood.

We come home, proud flesh showing golden on the scales.

Sockeye, Steelhead, dammed and gill netted, hunted by fish hawks.

We are impaled upon talons, taken up into fir trees

and eaten.

Beaten beautiful as seven billion Christs stumbling toward Golgotha,

we come home bearing the colors of fire across our backs.

Follow the scent of our Mother’s blood home,

we fertilize eggs and we die.

The carcass rots.

Young men called barefoot to the river in the heat of day are offended by us

and move on.

I am satisfied with that.

five

I will die at sunrise with the sky

red as a salmon lying on his side in a bed of coals.

There will be a little wind,

just enough to stir the oak leaf curled in the palm of my right hand.

When I die there will be phlegm in my throat.

The left nostril will be closed to further breath

and the right ear be so full of fluid

that breath itself sounds indistinct and vaguely sacred.

Hearing this sound I will enter into a kingdom of silence

and be offered a crown.

The Alone is alone with itself, has always been alone and always will remain

but you can find me here in all this beauty,

a blowfly sitting on my head

the color of a sapphire sewn into the crown of a yamaka.

I am satisfied with that.

.

.

PRAYERS IN WINTER

one

There is no difference between faith and unbelief.

Words are bloody rags placed on an altar.

“I believe, I believe…”

Beliefs are dead men slow dancing with worms, ashes raining out of their eyes!

Every prayer, including this one, a tsunami of self pity

a rogue wave in a daub of spit!

two

All day our faces are gulfs of green undrinkable water.

At night coyotes hunt the river bank for a life more quiet than their own.

Ten years ago you told me

“Come to the river in morning, among grass widows, in blades of light.

Come repeat a name composed entirely of water.

Whisper these syllables into the river not as prayers

but as breath let go of, not expected to return.”

Now you say

“Don’t try to find me where I’ve always been.

Look for me in dangerous places where the poor cook their own hands

for food!

I am the poor and the dead. I am meat in the fire.

Only when your tongue is taken back into the mouth in ashes

can you speak my name again.

Only when the roof of the mouth collapses in fire,

and the skull is broken into, robbed of everything

it possesses,

only when you are empty as the endless canopy of sky

can you kneel like a drunk man

amazed to find the full moon floating in a cup of wine.

Only when you can see the mountains of the moon,

bear witness to a light only the blind may see,

sing words only they can sing whose throats have been cut,

only then can you speak my name again.”

three

There is an oak tree planted by the river

so old only its leaves know the world still exists.

When I sleep, I hear the west fork of that river

and smell it in the fine hair on my wrists.

There is something in me wants to be that cold,

wants to come back to itself in deep water

where the river curves and the bank is undermined.

There is a quiet that goes on gathering in the river

until it touches a man between his shoulder blades and he wakes.

But there is no meaning in this world.

There is heaven. There is hell. There is purgatory

and there are hallways leading between them.

You tell me

“Every house is on fire!

The moon is dancing naked on the roof ridge

with all her feathers fallen to the ground!”

You say

“Throw off your blankets! Your sheets are in flames!

The bed where you are sleeping is now the unmade sky!”

.

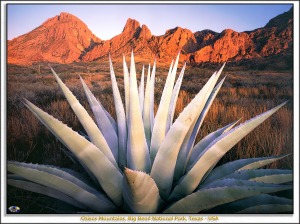

AFTER NIGHT SWIMMING IN STEPHENS CREEK, TEXAS, I AM CARRIED UP LIKE ELIJAH INTO HEAVEN

As they were walking along and talking together, suddenly a chariot of fire and horses of fire appeared and separated the two of them, and Elijah went up to heaven in a whirlwind.

2 Kings 2:11

for Carol and for David Spero

There is a quivering in the creek water

like the flanks of a mare in heat and in the pasture behind the log barn

there is vibration in the blood of the seed bull.

Hawks circling the moon watch the bull lift himself

on the backs of heifers

where he lays his head between their shoulder blades to smell

the quiet in their sweat.

In air thick and damp as a lover’s tongue there are tremolos of fireflies!

There are teeming wings of mosquitoes

as a million gnats too small to be seen are carried over treetops

in heated waves of breath!

I am joined in air by web worms,

by spiders climbing into oak trees, making sails of their silk.

Together we throw ourselves into the sky

where the moon is naked as a stripper’s breast!

Moonlight the color of skin stretched wide across the bottom land

where the ground slopes back to Stephens Creek

and javelinas come to rut.

In every cell of the captive locked so long inside of freedom, there is a tingling.

I am ready now for the moon to take me

in waves over pine thickets, over the river dammed and coiling, the color of a water moccasin.

I am flying!

I am carried away from San Jacinto County, north to Palestine, Texas

and beyond!

I am flying!

Anyone who welcomes me now, I welcome as my own self

and give myself to you in return.

As the heart of a man should be, mine is!

As the heart of a man should be, mine is!

.

SEVEN PRAYERS WRITTEN NEAR WEST FORK, ARKANSAS, IN THE SPRING OF 1974

I WILL LEAN INTO YOUR VOICE

I will drink your voice as a willow drinks the wind.

The terror of your nails!

The meat of your presence!

The seed bull enters his herd with a trumpet!

Grackles fly out of maple trees, shaking limbs as if in seizure.

The magnificent Eye that sees all creatures afloat in Itself

sees me!

I want to run my hand over the nylon covering your void.

Let me call your name!

.

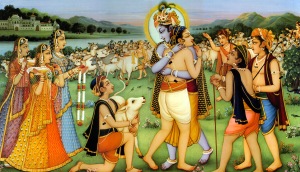

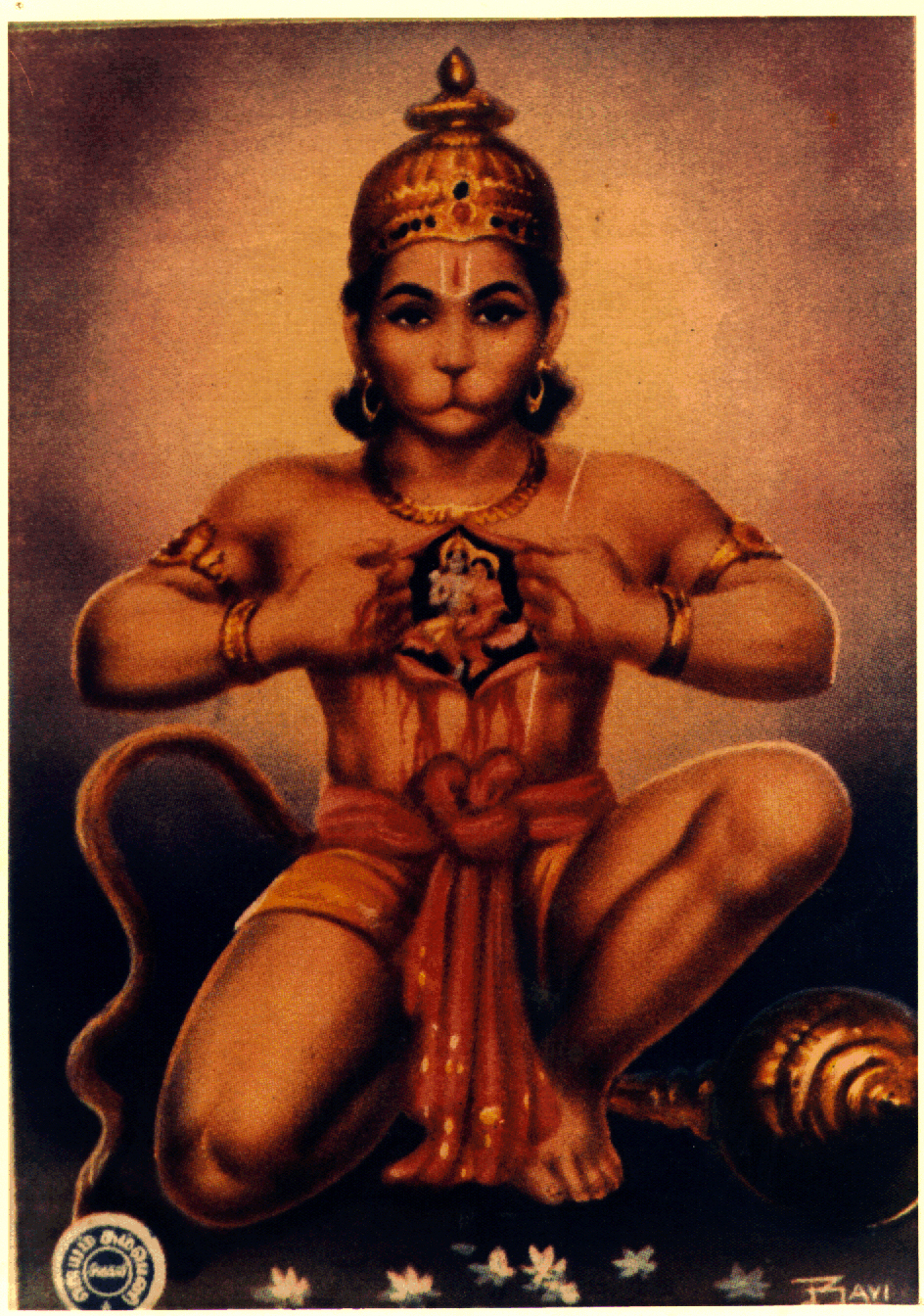

PRAISING KRSNA

Standing on a lake, playing his flute,

golden dhoti waving, Krsna is giving birth to wheat fields in the air.

Worlds, men and women tangled with stars

are streaming from the flute!

He speaks his own name and universes leap into being.

He keeps quiet and worlds gather back into Being.

He stops playing and eats a mango.

Over a sourceless, sounding lake he walks

every footstep leaving a child waking up in the water

of the Mother’s womb.

We are praising you Krsna,

praising you Krsna,

Krsna!

.

.

I LOOK IN THE INFINITE DIRECTIONS OF THE EYE

I look in the infinite directions of the Eye.

See your face upon the Earth,

the circle of your mouth,

your teeth like geese whose beaks point toward the sun.

Hear a caravan of wind, a shipment of breezes,

thunder carrying your Voice over the farms.

You are the Ark and the flood that lifts the Ark.

I am calling you like a tree frog calls for his mate.

I am calling like a cricket to the moon.

I want to be stripped of limitation, forced full of lights.

I want to be a raining presence of affection,

to stand naked before you

and give my self wholly to the river off your glance.

PRAYING IN A HORSE PASTURE NEAR MIDNIGHT

You enter through a wound

going down into the world

where fire walks, embodied in blood.

I walk into the fire and I burn

upside down in a suit of ashes.

Near midnight

I drink words from a broken cistern,

words and ashes mixed together.

I want the earth never to have existed!

I want colors going back into light!

I am afraid of little breezes touching my arm!

See wings made of moon light beating in the dark!

Something in me wants the iris to float out of my eyes,

wants to be old and surrendered to the sky,

give up to the floating scenery I am described by.

I want that!

I want to disappear, become all this.

I want to be with you and to know you.

Come down to this pasture where long eared donkeys bray.

Come down from the tower of the trees

or bring me up.

.

HEARING TREE FOGS IN THE RAIN

Hearing tree frogs in rain, I draw back the curtains,

let their clear syllables fall across my boots.

Last night we slept together touching ankles.

Now I stand at this window

holding in my hands the green light of cedars.

.

.

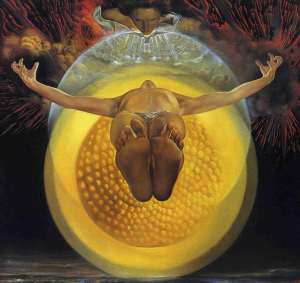

I SPEAK OF THE NEW BIRTH!

I speak through a cylinder of foam

birds raging in my throat.

A season of nails falls from my hands,

my feet.

The sky slides into my shoulders.

I am not this, I am not that!

The hundred angles of my smile attach to light.

I speak of the new birth!

Nothing is tangled.

The stars are stars, after all.

The coil is a river and the river is my self.

Watch for me, where I fly in the body of an oriole,

an answer without a question!

.

PRAYING BY A CATTLE TANK

I want to be touched by the nameless Presence.

I want my lips to be leaves of fire!

But there are flies on the surface of the cattle tank.

A mare with a belly like a church house has come down

to drink water.

From where I sit, I see

the jawbone of a cow that bloated in winter and died.

See a blue jay, everything eaten but its feathers!

I hold my hands up against the land, the sky, oak trees

without end.

.

WORDS WRITTEN TO FRIENDS TOWARD END OF WINTER, 2015

for Carol, Rob, Aja, Amidha, Michael

one

The world is memory.

You tell me about the squirrel you found, fallen from his nest,

hairless and smooth as a scrotum.

Now I remember that squirrel as my own.

Cry for him.

Off and on for the rest of our lives we go on crying.

We think we are stranded but we are moving at the speed of light.

Believe we are unloved while the Mother’s hands are

busy holding us.

Know with a certainty we only have a few years left to live

but we died a century ago,

only it made so little difference we never noticed.

two

Catching sight of God,

it’s like seeing a deer in the woods.

The colors are not impressive at first glance.

It’s God’s deer not Walt Disney’s.

If you’ve never seen a deer

you might miss it entirely or say to yourself,

“That can’t be a deer.”

three

Yesterday we walked to the river

one of us immersed in pain, the other aware of a unity.

The white water in the river below, the ringing of the hillside to the north.

High pitched trilling in the ear like 10,000 digitally recorded crickets.

Pixelated visuals of fir trees, dirt road, low hanging cloud,

all composed of sound, light, and energy in the body.

The body itself is made from pin points of light oscillating fast

as a moth’s wings flying into fire!

No difference between suffering and elation

between your body and mine

between the river below us and the sky.

four

My friend, despite what you say, I believe you are capable

of performing super human good deeds for all seven billion of us.

All of us at once, yourself included.

The common human heart may appear shallow as a grave

but it will open wide enough to hold the universe!

Our sun, our moon, all our stars are small as teardrops

inside you.

We will be buried inside ourselves forever

or we will burn, we will burn, we will burn

until we go free!

five

I don’t want to ever go past love.

I want to stay where love is.

It’s like treading water in a pool fed by springs

coming up under us,

not gently but churning the water in a muscular way,

the currents wanting to lift us all up

forcefully.

six

God has seven billion pairs of eyes but he is blind unless our eyes are open.

He doesn’t have a clue what he feels

unless we speak for him.

.

BUMS ON THE ROAD

“Tonight I am a child. I do not know that the moon is not the sun.” Rafael Stoneman

1971

I was hitch hiking from Oklaunion,Texas to Ellenville, New York

telling people about Jesus.

Dime in my watch pocket, the cost of a pay phone having risen that high.

People are mostly kind, give me food to shut me up

as if a man couldn’t preach with his mouth full.

Nearly died of dysentery in Ellenville

eating out of dumpsters what fell from the rich man’s plate.

Stole a jar of peanut butter while I was on the road

believing it righteous to even rob a bank in the service of the Lord

but a broken hearted man just out of prison taught me better.

Said, “Pretty boy like you don’t want to go anywhere near jail.”

One of very few converts that I made.

He was weeping beside me in his mother’s Buick

not for crimes he’d done but for the mother dead and buried

her hair grown so long in memory it nearly touched the ground.

Preacher in Brinkley, Arkansas

first put me up in a railroad hotel, then had me arrested.

I’d persuaded the youth director of his church to forsake all

take to the road with me!

24 hours in a drunk tank in Brinkley

before they drove us to the county line,

me and one old man the scriptures could not reach

so full of shame he could not help but drink himself

to death.

When I was a boy, I wanted to be a hobo.

Back when they all had long Bible beards

black as Chinese rivers in danger now of catching fire.

I see kids on the highway

20 years old, leaving home without their teeth.

Mouth sores like a leper’s, eyes like campfires built inside of dripping caves.

Where I live, in winter the sky is white as fish belly,

cut open with a folding knife, water always draining out of it.

Travelers keep dry beneath the underpass that leads to the river.

Driving by in my work truck I sometimes give them a dollar

but more often try to time it so I don’t get caught by

the light.

Crossing the Columbia from Washington into Oregon

I feel a distance come up in me.

Feel the space between the sky and what I call myself suddenly

come to nothing.

Maybe I am seeing through the eyes of a stranger on the road,

feeling the common and the aching human heart

that wants to free itself of everything

or die.

Whether it’s Ripple wine or Fiji water, all of us are drunk

on something.

Then we’re dead as any traveler found frozen in a culvert

by some lonesome railroad track.

There is joy in knowing this. There is joy in knowing this.

That is what I feel on a bridge of fog between two states.

But by the time I cross the river into Oregon, the stranger’s heart is gone

and there is only sky.

The Bible says we have no name that can be repeated.

It says that living with tears is also living well.

Even God sleeps in a rent house and may be torn asunder.

Sometimes I feel shame having lived this long, awake in the night

with so little still to give.

But here are my empty hands in friendship.

What I have is yours.

WORDS WRITTEN TO FRIENDS IN WINTER

A small bird will drop frozen dead from a bough

without ever having felt sorry for itself. D H Lawrence

1.

First 37 years spent in solitary confinement

rolling dice carved from finger bones

against an unforgiving wall.

Let out from time to time

to circle the prison yard.

2.

No brain for science.

Forced by nature to relate everything to God.

Layers of imagined specialness,

all very complicated.

Getting old now.

Falling back on what set this world in motion.

Whatever Love is,

the only God I want to know.

3.

Selfishness at the root of every body.

Take care of my own self first.

Fight for the last remaining breath.

All very tiresome in the end.

The body stores so much tension it can’t relax.

By the time it dies, its face belongs to someone else:

to this man created by a tension

held so dear.

4.

Friend

when you came to my door, your arms were open

but I was asleep.

I have climbed into pine trees,

scanning distances the colors of cerulean frost,

hoping to catch sight of my own eyes.

Maybe you called my name but I could not hear

for all the mockingbirds.

When you left, even the crows left with you.

Even the blue jays are gone from my door step.

No one singing now.

There is no pain other than being here without you.

All other pains are rolled into that one.

5.

Behind all of this, an embrace, a smile, a welcome

home.

At the right moment, I will not be afraid.

What is broken will be knitted back together with needles

of light.

I know this.

6.

So interesting now to hold the hand of the one I love

to feel it as a woman’s hand grown old

but also a girl’s,

a dry leaf, a flow of air across the palm.

In the dark

we can’t tell whose hand is whose.

7.

We are all illegals here

all of us homeless with a hand out.

Help me cross this river, Friend.

Water is streaming out of my body red as blood.

Hold me one time in your arms and tell me I am

precious.

Once will be enough.

8.

Being on time for God is important,

being awake when he passes on his morning walk….

but luck has so much to do with those who catch sight

of him.

No matter how diligent we are

we drift out of sleep just in time

to see the moon passing full across the window

pane.

9.

I sympathize with your friend who shot himself in the head

but let’s not do that, just yet.

Fellow I knew recently hung himself.

A good man, you couldn’t miss the kindness in him.

Battled depression for years. Fought it hand to hand.

The end of a long relationship must have played a part

but the final blow

was the dean of the local college,

where this man painted, cleaned, repaired the walls.

The dean announced it was likely the school would have to close,

all workers thrown into a fire.

That good man went home, wrote some note to his children

and hung himself for a friend to find.

Now it seems the dean was hasty.

The school won’t close after all. They say that school never closes.

How could it?

10.

Hope is not essential.

Sometimes there is joy and ecstasy.

We feel a pointed participation with our Existence

as a person with plans unfolding.

Sometimes there is an ecstasy with no plan.

Just seeing the moon pass across a window pane is enough

to justify the universe.

Other times we are in pain,

rolling in our bed sheets as a caterpillar spinning its cocoon.

Or we feel we are taking a light nap

aware of what is happening around us but uninvolved

with it.

Either way, risen or set, the moon is there.

The moon!

11.

Not allowing ourselves to tunnel out of prison is important.

Not rolling our bones into a past or future.

When we fall in love, it always happens where we are

not where we ought to be.

We look up, for no reason that we know, and there is Lord Krsna.

Or in my case, there is Carol

or there is Krsna dressed as Carol or Carol dressed how Krsna would be dressed

if he were dressed as Carol.

I want to give back everything I have stolen from my Self

saying it was “mine”.

Let me lay it down on the kitchen counter, where I find myself

naked as moonlight

waiting for water to boil.

.

PRAYER AT CHRISTMAS, 2014

I will kneel before imaginary gods

Taking their blue hands as wings

And I will fly as one of them into persimmon trees

To sing the sweet fruit down

But the one I love more

Breaks the back of this world, hammering its vertebrae to dust!

I will sit before a willow fire

Banking heat, storing what light I can

And when night comes with increase of darkness

I will hold cupped hands against the afterglow of that collected light

And sing the songs old men sing before they curl into a bed of ashes.

But the one I love more, imagines this world.

Then comes with wrecking balls, comes with hammers, comes with demolicious fire.

There is nothing better than to wake suddenly in flames!

Walking down the river road in a wedding coat of fire!

These words are memories.

Hearing them, a blue jay will turn his back on words

And lifts his wings into a sweet persimmon tree.

.

LINES WRITTEN AFTER READING “PARKINSONS DISEASE”, BY GALWAY KINNELL

They say our hearts are hard

but inside that stone is a hollow

filled with blue industrial diamonds.

After we die, our jaw bones go on grinning.

The skull empties itself.

Magnificent human eyes give up space

for the moon to see through.

We humans do not look away

from our own faces decaying in varieties of mirrors.

We extend a hand in welcome, even to death,

making nothing of what is already nothing.

I say that all of us will falter, all of us will kneel,

and all be left standing.

I say there is a sky, blue with diamonds, coming down over us.

There is a singing in tongues only mountains understand.

There are hands of fire reaching out for ours.

EVERY MOMENT I AM KNEELING

for my wife, Carol

To strangers and to moths gathering around fire

my common heart is opening.

In every rounded corner of the world there is a laughter

I can hear.

There is a joy I share with falling leaves and sparrows.

Inside his prison cell, the condemned man is awake,

overcome with joy.

His floor is worn smooth with solitary dancing.

The bags under his eyes are packed with sand to stop the river overflowing.

Can you hear those church bells ringing in the palms of his hands?

There is a happy static jumping inside the blood

and across his rib cage, pastures waving, fireflies humming!

The pain that comes with love is taken down into the body,

locked in cells designed to open.

That pain is free to go now!

Born naked into fire? That pain is forgotten!

The pain of Earth confined in solitary space,

all that is over now!

From here I see a billion suns clustered as her crown.

Some like to take the shape of planetary nebulae falling past the world

as flaming dust.

I like to follow the blood, returning to the heart.

Every moment I am kneeling with an ear against my prison wall

and the beating heart I listen for is yours.

AFTER GALWAY KINNELL DIED

These poems may not be worthy of having the name Galway Kinnell connected to it but I have to thank him, as I am able, for the gifts he has given me.

October 29, 2014

one

The day Galway Kinnell died, a finger was found in the East River,

Queens, New York.

The finger of a giant, cut from a muscular hand,

still bearing the mark of a wedding ring.

A little Honduran boy playing by the river found the finger moving in the current as if it were stirring a bowl of sky.

Every time a barge would pass, the East swelled awake

and the fingertip was lifted high enough above the waterline

to touch the river coming down, making a water ring.

two

One hundred yards down, under Throgs Neck Bridge,

where she was raped ten years before,

a mother is ready to forgive the river its indifference.

All night, after Galway Kinnell died, she stayed awake, reading

The Avenue Bearing the Initial of Christ into the New World.

All that night she was crying, until river gulls,

who would steal breath from morning just to keep their young alive,

woke her.

Quietly then, she took her left hand into the right,

holding both as her own and she was healed in a moment by Saint Galway!

It will not be a rapist’s eyes she remembers now,

though they were sharp as folding knives flicked opened with a vengeance.

It will not be the smell of pork flesh in his teeth, she remembers,

but how the heavy woolen overcoat she wore that night,

cushioned the ground, as much as it was able,

how tug horns, in compassion, went on blowing in the fog, covering his curses and his threats.

That coat is black

with silver threads like trails of stars falling through a moonless night.

She wears it now, as if the river is a lover she was assigned to meet.

At ten o’clock the morning after Galway Kinnell died,

when the flat October sun is so intense, she has to shade her eyes

to see galaxies of gnats and water walkers swarming on the river.

three

Twenty-nine hundred miles away I am standing in the White Salmon River, Underwood, Washington,

where cliff swallows are calling, “Galway, Galway…”.

Eleven silver salmon in the white water,

six of them dead, five scouring trenches in the gravel bed,

ready to spawn before they die.

The smell of the living and the dead, rise up together, braided with the river

to make a perfect twelve.

Standing in white water, cold coming through my boots, drawn up calf and thigh bone

clenching its fist around my ball sack,

I pray:

Mother of creation,

All eruptions of consciousness,

including the human animal thrusting disease into itself,

All planets, stars, the space between atoms

in which galaxies flourish,

All currents, energies, waves of light,

trillions of created souls, each one different from the other

as Hutus are from Tutsis,

All of us born together in flame and blood through a single red vagina,

as the Mother is born of Herself.

All of us are merged in a Unity beyond conception!

This is my prayer.

four

It is unkind to tell those who suffer,

that happiness is just another kind of pain.

But standing in the White Salmon River,

knowing the Mother as my own self,

the air between us so erupt with joy, I feel I am being beaten to a kind of death.

I tell you this joy is so intense at times, I hardly care.

.

http://www.wnyc.org/story/85403-philip-levine-reads-galway-kinnell/

GO TO HER

…I brought him to my Mother’s house

to the bedchamber of the one who conceived me.

Song of Solomon 3:4

Go to her.

Leave the flesh waving behind as if it were an acre of maize.

Float out to Her, calling her name.

Your voice is a morning glory opening in the throat.

The name forming on your tongue,

one thousand syllables of falling water.

We are drawn from our Mother’s well

fed by Her spring, hidden until sung for

in the folds of Her.

.

THE GHOST OF WATER

There is a way through earth known only to water

and to the water witch with a pliant branch of willow in his hands.

I am a ghost of water

whispering into my own good ear

all I need to know

how I live and move and have my being in a Gulf

how all of us are bathing in our selves

the light we see by

streaming from our own eyes.

THE WOMAN ON THE ROAD

for Michael Johnson, for Aja, and for Rob

April 7, 2014

Yesterday took a walk to the White Salmon River. Felt lit up as usual down there, praising God above the rapids, a fat man swollen with joy. Coming back met a woman maybe five years older than I. Skin of her face worn thin. Had the look of a logger’s widow, hands nervous as a knitter’s, hair pulled back into a pony tail like a girl’s. Stopped to talk to my dog, to tell us why she was on the road.

Someone close to her, she didn’t say son or grandson but I assumed it, was having troubles, had disappeared on 114 just across the river gorge, the road you can hear winding past a plum orchard, all in bloom now, pink as whore’s eye shadow. He’d driven away on Thursday in a white pick up but never arrived at work. Not seen or heard from since. So she was walking the river looking for a truck gone over a cliff, down to the water. This road we walk is closed to autos, the bridge over the river burned years ago. Tells me she used to ride it bareback on an appaloosa mare, all the way from BZ Corners, maybe 10 miles away. Now she’s looking for someone she loves, someone she believes dead by his own hands and still she is smiling, telling me this story, though her smile be thin and full of pain.

Minutes later I see a young squirrel, still immature with a tail that has not yet flared at its tip. He is sitting on the limb of a locust tree eating dry seeds that formed before he was born, letting the pods go spinning down like propellers to the ground. I hear him give a quiet little bark, then throw his head back and howl like a coyote, six inches from snout to root of tail. Those who live long enough know this world likes to eat its young, murder and give birth to them again and again. Still there is a joy here we need not, can not live without.

When I get home I realize I am exhausted and take a nap. Feel fine now. These words are a prayer for the woman on the road, for her sons and grandsons, for anyone who might lose his right hand to a chain saw and not be able to work again. I can feel another’s pain now but it doesn’t take hold. It is like the memory of a tooth pulled weeks ago, a ghost standing among a congregation of other ghosts, waiting for something they have earned but no longer want. This world is a wedding feast and crucifixion. Always has been and always will remain, as long as human beings are still human.

.

THE LAME LEAP LIKE DEER

“The lame leap like a deer, and the mute tongue shouts for joy. Water gushes forth in the wilderness and streams in the desert.”

Isaiah 35:6

“To live in the world and yet to keep above the world is like walking on the water.”

Hazrat Inayat Khan

.

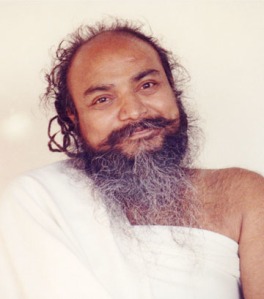

Shivabalayogi,

you make my heart a place of worship,

an unfenced pasture where creeks stream together in a confluence

of laughter.

My heart is a drum for singing your name

and you are its drummer.

Your voice is released in waves and I go walking on the water!

Bones becoming light under the skin, the hollowness inside them filled with laughing gas!

There is no one above me now, no one below

only you.

You say I hear your voice when I listen well to my own.

I am listening now. I am listening.

You say

I came because you waited all your life for me.

Everywhere I look I see your face as fire

with its green radiance.

You tell me:

The falling bird remembers how to fly.

The heart works well, once it has been broken.

Now the ground opens under my feet and I find myself suddenly in air!

Shivabalayogi

you take me to the limits of the sky

where there is nothing left to leave behind.

Out where there are no names and no in coming breath

is the dome of a sky,

black as polished obsidian and full of stars.

This sky seems infinite in all directions but is not.

What seems to be an endless sky is only the pupil

of your right eye.

TWENTY EIGHT THROW AWAY POEMS

MORNING WITH BIRDSONG

With all this memory left in me

how can I go to sleep under your southern wing?

With all this blood, how can I hide my face?

Only if you say clearly

“You have no face that is not my own.”

can I put myself to rest.

.

.

MORNING PRAYER FOR CAROL

“Everything that touches you.” The Association

May she sleep well at night.

Wake without pain in her shoulder.

May her knee and hip not cry out, bringing her too soon

to this world.

May blue jays speak respectfully at her windows.

Let there be peace in her morning contemplation

a perfect cup of coffee in her hand.

May she enjoy everything she sees and hears, everything she touches

and tastes.

May she always delight in the face she sees in her mirror.

Let the first incident of the day that would disturb her peace

not happen.

Let her go at her own pace and never tire of beauty.

May beauty flow in her as mercy and as a joyful song.

May she enjoy her garden as she does her flying dreams.

May there always be harmony between us and trust and may our eyes be creased

with smiling.

.

.

CAMPING OUT IN A PASTURE

1975

Though the house is only a hundred yards through the woods

we lie down on damp ground

to draw into ourselves the cold life of stones

on foot below fescue.

There is a Quiet coming up

like a mountain blue with distance.

We try to know

the solid ecstasy of rocks, floating ecstasy of leaves

the clamorous ecstasy of creeks.

I say that our lives are eternal and there is nothing

we can do about it.

.

.

EMPTY HANDS

1978

I hold up empty hands to show you

what I have made of myself

in a city where even wetbacks get rich

and every highschool graduate has a scheme.

I hold up hands and long arms

empty as cement beaches.

In the backyard wild onions come up.

Bluejays like unoiled hinges sing.

My eyes open on an expanse of GI houses

empty empty empty

meaningless repetition like the ticking of a watch

on the wrist of a freshly buried man.

I hold up hands full of nothing

but the breathing winds of Houston.

.

.

CONTEMPLATING A CHRYSANTHEMUM

All that I am, all that I know I bring with attention

to these chrysanthemum leaves.

In the side yard a pigeon and a mourning dove

preen themselves in the green crown of a willow

tree.

.

.

RECALLING WHO I AM

So much has changed

but the ache of knowing I am still here

is the same.

The heart opening wide as a grave digger’s yawn

trying to take in more than it needs to survive.

.

.

THE OTHER IS MY SELF

We share a common existence, living in seven worlds at once

and in every world there is a price to be paid for love.

What I cannot imagine or hope for is all I have

to offer you.

.

SITTING IN THE WOODS OUTSIDE KINGSTON, ARKANSAS

You have to wait

wait until it begins to happen.

The black beetle rolls a ball of dung at your feet

intent upon it as a lover after his pleasure.

In a circling breeze are

two saplings beautiful as adolescent girls before the fear

of happiness comes.

They dance together, one touching

the other.

After an hour you are invisible

and the deer that you don’t see, does not see you.

In a hollow walnut tree the owl startled from its sleep

speaks a name in the Ojibwa language

you recognize as your own.

.

.

63 YEARS OLD, WALKING ON COOPER ROAD

63 years old, walking on Cooper Road

two loops around the graveyard and home.

Sun in the west through Douglas fir and second growth oak.

My shadow on the blacktop, rounded in the shoulders

as I remember my father.

.

.

I DRIVE FIVE MILES WEST ON 114 TO KAYAK IN DRANO LAKE

I drive five miles west on 114

and paddle to the drainage of the Little White Salmon River.

The water clear down to bedrock.

Spread wings of the sky cover the surface of the water

until a stroke of the paddle

breaks the perfect mirror with a wave.

In the pool close to the fish ladder

I watch salmon try to leap the dam, go home to the river.

A thousand more, dead or spawning, bump the plastic hull

of my yellow kayak.

.

.

SUMMER CORN

1985

Inside your voice is another voice

saying, “Come in here. Come in…”

Inside that voice a third voice is singing about sunlight dancing

along a certain ear of corn.

Inside every yellow kernel is laughter, is water falling

water falling, clapping on a rock!

.

IT WILL BE THIS WAY

Texas will secede from the Union. There will be a killing!

The profit of the Lord shall not be made less

than any another man’s.

The Red, the Brazos, and the Trinity will be gutters of blood.

The Big Thicket will be burned and the Salt Plains put to use.

Those who lie with the Babylonian Whore cut their own throats!

Every man, every woman, every child

who bends a knee to the wrong god

will be cut down in open fields

and left to the sky!

Hair and teeth rise up in plowed furrows!

Jawbones go on talking for a thousand years!

God’s voice is a devastation of cornfields!

.

.

THE LIGHT OF OUR FACES

1987

one

When I kneel to this world

a fire burn in the joints of my knees.

Streets once warm and moist as a woman’s thighs

turn cold.

50 gallon barrels in alley ways where the homeless burn

old news.

two

I heard this on the radio in Hood River, Oregon:

A 76 year old man dying of cancer was caught laughing out loud

at his own funny shadow on the hospital wall.

Told his wife he would rather walk once more alone on Mount Hood

than drink death for half a year in bone colored rooms

where people wear masks.

So a friend drove him up to Cloudcap where he walked in falling

snow

and was found six months later become the color of water.

By the light of our own faces

we may look straight at the terrors of this world and be found clear

as water.

.

.

FOR JEFF IN 1988

In the beginning there are rainbows inside of eggs.

The moon is small as a lentil.

Earth is the right eye of a sunfish.

I wake in darkness with my own arms around me like a fetus.

Heartbeat is a voice whispering secret names of other selves.

Morning singing to me like a Mother.

.

.

DAWN IN LATE OCTOBER

1970

It is dawn now in late October.

I have been awake three hours drinking tea

and studying the slope of the roof next roof.

I will have oranges for breakfast.

Eat the morning slice by slice.

.

Your face is radiant as shucked corn

Troubles blow away from you like chaff.

What has happened?

.

.

I FEEL SORRY FOR HER

1979

I feel sorry for her.

She has fierce periods of blood

arthritis in her knees.

Her skin breaks out

and she cries for no reason.

Her face is always cloudy as water about to boil.

I make sounds in my sleep

wake up shouting about Jesus.

I am helpless. There is nothing I

can do to save her.

.

.

SHE NEVER MADE A MAN HAPPY

1979

She never made a man happy except afterwards

when he remembers escaping barefoot

down her back stairs

gray paint blistered and cracked in the soles of his feet

like walking on nails

except he is laughing out loud as he runs.

.

.

DRIVING THROUGH IOWA

1979

We are driving over a rise of ground in Southeast Iowa.

Furrows on both sides of the road half full of snow.

Looks like ten thousand bodies wrapped in sheets

laid side by side in the fields.

Above the flying car, the sky turning blue as a crow’s

wings, we are reaching out toward two infinities.

At dawn we cross the borderline.

.

.

WALKING IN THE STREET AT NIGHT

1979

Evening breezes blow though my window

lift the curtain, letting darkness in and out.

I walk the streets

knowing what I sense in the dark is my own elaborate self

that is dying.

Elm trees in the green night look like negatives of photographs

of hands on fire.

The pavement is leading me past houses where desires are kept

locked in drawers with loaded guns.

I don’t know where I’m going, where

I will end.

I walk in the dark suffering the blows of headlights.

.

.

BEN HARRIS IN 1957

Ben Harris bends over his coffee in the dark

of early morning.

Dandruff falling from his head into a cup

full of stars.

His shadow is thrown by light from a kerosene lamp

down wooden steps into the chicken yard.

.

.

LITTLE POEMS WITH LIGHT IN THEM

1979

one

Light the color of a heron’s wings, light com-

ing from a clearing in a cloud bank.

Blue portuguese men of war light.

two

Let me tell you how the polished body

of a jellyfish gives off light from deep-

er down deeper down

like the eye of a buck deer embedded in glass.

Let me tell you how my hands are drawn to your body

like teenaged boys to an empty grave.

three

Go barefoot into your own yard, into your street,

where chinaberry trees flame in the green morning.

Go early before you have to,

when cold strikes the soles of the feet

runs up the legs following the spine.

Cold shooting into the brain, green joy flaming

in the temples.

.

MUNG BEANS SPROTING IN A JAR

1979

Inside the shell the life is waking up.

A white coil lifts, tiny wings begin to open.

When the coil darkens in the light, the wings turn green

spread out as two hands of a priest.

We are all, we are all that light.

.

FOUND POEMS ABOUT ADMIRAL ISOROKU YAMAMOTO OF THE IMPERIAL JAPANESE NAVY

1982

A Son Remembers His Father

He often took a bath with us.

He was very kind

and washed our backs and faces.

In the afternoons he would play catch ball

with us.

Though missing several fingers

he played catch ball very well.

The Admiral Thinks Of Retiring

In autumn I will return

to the house where I was born.

I will read the books my father and grandfather left.

I will grow vegetables and take care

of the chestnut tree.

He Regrets Making His Men Practice Dive Bombing

With every dive their lungs bleed, their lives

are shortened.

It hurts me

but I do it for my Emperor and my country.

On The Eve Of Pearl Harbor

All my men together are one person.

What the world will think, I do not care.

I am the sword of my Emperor

Days Before Being Shot Down And Killed

I have killed quite a few

of the enemy

and many of my own men have also been killed

so I believe it is time for me to die.

But I am the sword of my Emperor

and I will not be sheathed

until I die.

.

.

TO THE HUNDRED MEN DROWNED IN THE OLD AND LOST RIVERS, NEAR WINNIE,TEXAS

1973

A hundred drowning men gave themselves

to The Old and Lost

gave their bodies to the gar

gave their heads for snails

the coils of their tongues to speak for

a strangeness in the river.

Carried into tributaries, into ferns

and tabernacles of roots

a hundred drowned men float on swollen backs

giving up their voices to be ghosts of water.

Overhead, the white crane circles.

.

.

BEFORE ME I SEE A LAKE OF FIRE

1973

Before me I see a lake of fire,

one fish leaping up with scales silver as coins.

I see the coins dissolve into a mist of atoms

and the atoms condensed into light.

Inside this light are rainbows,

are moons and people walking

and when the light enters the water

it is a fish again!

.

.

TWO FLAT TIRES, TRUCK IN DITCH, Fairfield, Iowa 1983

Two flat tires, truck in ditch.

Tooth chipped when I fell down looking for keys.

Everyone I love is sleeping 800 miles away.

This will all turn out to be exactly what I needed.

BEING HAPPY AT 63

.

After painting a horse barn all day, I drink tea in late afternoon

with Carol,

letting go of what can’t be held in her hands.

Eight hours gripping the rungs of a twenty-two foot ladder,

now that ladder falls while I remain in air!

We hear cicadas singing in shrubs along the fence line,

so loud they must be inside us.

Delighted now in whirring air after years under the ground,

cicadas are rising in a mass, shedding larvae shells.

They are singing for their mates, flexing the muscles along ribs

of exoskeletons.

I offer my right hand to one who has landed in leaves of a hops vine.

She steps gladly on my finger that was broken in the Fall,

recognizing its curved rigidity as her own.

There is a joy years in coming that waits for us in the dark.

It fills the space we call emptiness which has always been full of stars.

There is an emptiness that is spring fed and overflowing.

There are eyes in the dark and wings prepared to open.

Whirling in the air, there is a joy coming in waves and in shattered lights

made whole.

.

AMISH WOMEN IN THE SURF

Littoral Women, by Kevin Schoonover

.

EASTER MORNING, MATAGORDA BAY, TEXAS

“Roll down the window and let the wind blow back your hair.” Bruce Springsteen

.

On Matagorda beach where cattle gather at night to escape mosquitos

and white calves lit by the moon

are taken by sharks feeding in the shallows,

Amish women come barefoot with their daughters.

Fully clothed as the day they are born again in water,

Amish women wade in the Gulf to their thighs.

Heads covered, skirts to mid-calf, dyed the modest colors of the sky,

they kneel to the wave that covers them,

knowing without believing,

that this is the Mother they are born from.

Fathers, uncles, brothers, sons walk the beach dressed in black

with their boots laced

or wait in rented, utilitarian vans discussing scripture,

the price of seed corn and harness leather.

Amish mothers in their early 30’s with teenaged daughters

walk to their waists in the surf

remembering mornings their waters broke,

when their skirts were saturated with the salt,

waves of pain taking them closer to heaven and to hell

than they care now to return.

An Amish woman knows how to plow behind a horse

and when called upon before first light,

will throw strong legs across her husband to help him

work the soil.

But on Easter morning,

touching hands with their daughters in the surf,

images of Anabaptist martyrs slip from the mind,

men burned alive, women with pikes driven into them.

Holding hands with their daughters, they come as close to dancing

as they are allowed,

careful not to cross into water too deep to come back from.

Mothers and daughters going down with waves between their legs, a rip tide tugging at the coarse cotton they are bound in.

Turning their backs to men waiting on shore,

nipples showing through wet blouses, pink as apple blossoms,

Amish women watch the sky come down into the Gulf

and the Gulf rising up in waves

to meet it.

.

THE FLOOD PLAIN

March 9, 2013

In 1969 I went to school in Nacogdoches, Texas, driving back and forth to Houston on weekends. There was a honkytonk I’d pass near Diboll called the “Tired Moon”. Well, I was 19 and except for communion wine had never tasted alcohol but I was drawn to the place by its name. Once I pulled into the clam shell parking lot, determined to go inside but came to my senses, believing if a guy such as myself should enter the Tired Moon he might as well be wearing a t-shirt that said, “Kick my ass for 5 dollars” and I better damn sure have the five. I was big and had the muscles of a working man but was always always told I had the eyes of a girl. A mistake to be born that way in Texas. Five years went by.

My first wife, Shelley and I were living with our baby daughter, Ananda Lorca, in a stone house outside Huntsville, Arkansas. Ananda means “Bliss”. Lorca is the last name of my favorite poet at the time. I wanted her to be called Lorcananda, meaning “the Bliss of Federico Garcia Lorca”. But no… One weekend we traveled deeper in the Ozarks to spend the night in Eureka Springs, a turn of the century town built over mineral hot springs, where, in the off season, you could get a double bed in a beautiful old hotel for $12 a day. We were planning to spend one night there.

The town had built a replica of the old city of Jerusalem and held a regular Passion Play for $1.50 per, but in the off season they weren’t playing. While eating lunch in a cafe I heard the rumble of motorcycles and saw at least a hundred of them parading into town. Soon the cafe was filled with large, ugly men and with women who had forced themselves into leather pants. Greasy hair, tattooed snakes forming the numbers 666, chains and cigarettes! I was eating with my head down like an evangelist at a banquet, literally minding my own peas and cucumbers, when I heard one of the women ask, “Are you stayin’ over Saturday night?”

The man who answered had a face like a fistful of teeth swimming in a bowl of chili. “No, I gotta be back to teach Sunday school in the morning.” It was a Born Again Christian motorcycle club. Had several more sightings of them in the years to come and was told by a deputy sheriff they were pretty good old boys as long as you stayed away from topics such as sprinkling versus baptism by immersion and the whole question of using real wine or grape juice in the communion service. God help the paid preacher or the Catholic stumbling unarmed into their midst. Twelve more years went by.

I was divorced and living with Ananda and my son, Eli Luke, in Fairfield, Iowa. Eli means “the Highest”. Luke means “Light”. So his name means, “The Highest Light”. We were driving back to Houston in our 1978 Datsun King Cab for a visit when I had a lapse of attention. I didn’t go unconscious or fall asleep at the wheel. I was driving perfectly fine but still ended up 300 miles off course in Paris, Texas. Paris was the home town of my former father in law, Peyton Bryan. I also had an uncle, a brother and a brother in law named Peyton and feel I understand them better for having lost my way. We stayed the night in a motel with a swan motif, pink chenille bedspreads and framed photos of the Eiffel Tower in every room.

We were eating breakfast early the next morning sitting next to two couples. Listening to their conversation I could tell the husbands worked for a big rig construction company and traveled from job to job with their wives. None of them seemed to know each other well. Even the married couples were strangers to themselves but I was struck by one fact, the wives were staying with their husbands, not running off to California leaving them with kids. Right then I wanted to write a country song about these folks which Waylon Jennings and Jessi Colter would sing. On a napkin I wrote the words, “She followed her man while he swung his wrecking balls from state to state. “ That was as far as I got. Twenty-six years went by.

In 2012 I remembered the Tired Moon, looked for and found the napkin I had written on. I wrote a poem in rhyme called “The Flood Plain”, still wishing it could be sung by Jesse Colter, Waylon Jennings having died some years before. But I admitted to myself that no one would ever sing this song so I rewrote it in a conversational voice from the woman’s point of view. It is somehow better for a poem to go unread than for a song to be unsung, I believe. The song was sad and hopeless but the poem ends with a possibility for happiness. I believe now that joy is as inevitable as sorrow. One comes as unsought as the other and stays or leaves as it will.

.

THE FLOOD PLAIN

One year in ten with bloated cattle washing on its back, the Brazos will engorge and try to drown us.

.

Two hours drive from where I labor, is a night spot on the Brazos

called the Tired Moon.

We got married there when he could still light cigarettes with his eyes.

Good luck was wished on us by women dressed as cowboys

living on the flood plain,

while fiddle music slithered through smoke and coiled around our heads

like lassos.

On that day I held a photo of my mother in her apron, unlit Marlboro in her left hand

like an extra finger.

Her hair was a cotton candy tower with a yellow rose of Texas in its turret.

In two months I began to notice that the pleasure lit between us was a fire

and the burning registered as pain.

Five years I followed my husband working big rig construction in thirty states.

He swung his wrecking balls from Lansing to El Paso and from San Diego

east to Galveston.

Six months a year we lived in trailers parked in clam shell lots

or in motels behind biker bars

where mornings you might see a stranger’s blood drying in the gravel.

Fire ants feeding on that blood were the color of the sun setting down through diesel.

Six days a week in false dawn, I’d hear him rise, let down his water,

draw a razor cross his face and throat.

Once I watched him kindly part the polyester curtains to look down and say a prayer

for all boom boom girls lined up for jail.

Standing in each others’ shadow, flinching from the headlights of a passing

Eldorado,

they were smoking Camels down to glittered nails, all their eyes as faded

as a blue tattoo.

I grew tired living on the road,

so we bought a trailer, placed it down among some willows grown too near for comfort

to the old and fickle Brazos.

From our bedroom you could hear the highway

and on moonlit nights hear coyotes ripping road kill neatly from the bone.

One weekend per month he was at home.

We sat at evening by the river, watched the sun set fire to willows green

and silver.

Sometimes he’d cry after his beer,

never believed he’d be this old and this alone.

Five hundred miles of highway in his eyes where the only thing on radio was static.

He listened to the road noise from our bedroom,

heard it howling through the marrow of his bones and knew

that even if he stayed he’d be alone.

So he called me from El Paso and he called me from Las Cruces

and he called me once from Phoenix, Arizona.

As he drove there were signs and there were warnings on the radio

of flash flood.

One hour east of Lancaster in the red Mojave Desert, where the mountains in his

headlights

looked like butchered white men bleeding on their knees,

he lifted his tired eyes to heaven like the two moons of Uranus

and there across the carcass of the sky, he saw the hand of God

start writing his parole.

He stopped his rig beside a dry arroyo where water once was flowing,

felt the floating dead he carried inside his body start rolling on their backs

and he saw, with a child’s expectant eyes,

the new moon.

Sitting in the cabin of his truck, the engine ticking

and the smell of grease softening the desiccated leather of his seats,

he felt the desert suddenly splitting open, with the ripe crack of a melon from Luling, Texas!

A fearful and a shuttering elation opened in his heart, as if the world was ending.

Dry lightning in the distance looked like Jesus on a palomino pony, come to save him.

But waves of river mud were also rising and he knew he could be drowned,

forever buried under sand piled six feet high against dry runoffs in the desert.

All banks could be broken in another flash of lightning,

giving way by force of water.

So he turned his rig around and started home.

Somewhere he got lost, drifting off the highway, found himself in Charlie, Texas

where the dawn comes on like peaches grown along the Wichita.

Thirty six hours without sleep, the dead within him washed with weeping,

he parked his truck under willows and saw me in a sun dress

waiting.

There were nights I drove two hours to the Tired Moon.

I drove alone to dance with strangers.

Straps had fallen from my shoulders. More than once the ribbons in my hair had come undone.

If you hear these words and think you know me, if my number’s written

on a matchbook in your pocket,

I’ll call it kindness if you keep it, if you keep it to yourself.

.

OCTOBER SONG

“I sing you this October song.” The Incredible String Band

one

Come walk these wounded streets with me, where maple trees leak sap in regimental lines.

Where leaves the colors of blood are taken by wind

and carried to the fire.

I am the wounded and the fire in which we burn.

But now the clear plastic over this world has been torn away,

enough that I can breathe.

Now everything is breathing and even the dead are alive!

Up and down the ladder of my spine, grandmothers carry baskets

of flame fruit,

their long hair coiled in a bun and covered with a sequined net.

Listen and you will hear even the dead

are breathing.

two

If you are crying, open your eyes and let them widen

til they contain the whole of the prairie sky.

A sky will open in your heart and the sound of wings

be like a river.

I say you will never be born again, never beat another child just because she cried.

You will not die of cancer.

If you are crying, let your tears fall into the simplicity of fire.

three

I am crying now.

People tell me I have the rounded shoulders of a man who labors in the dark.

My hands may be hidden by the blue gloves of a working man

but even while they hold a paper hanger’s knife,

my hands are worshiping the one I love.

Sometimes the moon looks like a puckered scar in a blue fog.

Sometimes the cool of night touches the bald spot on the back of my head

where an emptiness is shaped like the morning star.

I feel the cold of this world but when I can let the night be all there is,

the moon with a cloud across it white as a wedding veil

can make me weak with joy.

I carry a hundred thousand years of light across my shoulders!

The round stone of this world drops down through me

and I laugh like a river with gravel in its throat.

I am loving the dark face of the sky,

loving her painted circus eyes, her carnival lips!

four

For years I walked through mountains sharp as teeth broken under the skin.

Hungry enough to eat stones, a stranger even to myself,

I swallowed anything that would keep me warm,

put on religions like long blue overcoats.

And I loved women as if they were spun of wool,

born only to maintain my heat.

Trying to be what a man should be.

Failing that, I would lie down on the ground

waiting for a star to fall into the plowed furrows of my heart.

Spent bullets, knives, teeth fashioned into arrow heads

began to rise up through me!

Tomahawks, missiles, war poisons were brought to the surface

by the cleansing action of the earth.

So I was brought to the surface of this world and made ready

to step into the sky.

five

I wore the sky across my shoulders,

all the colors of a troubled Gulf, the gaudy archetypes of the end of time.

I could feel a sky come down over me

dung colored, river throated, green and heavy with hair.

I was crying, my voice ragged as a gull’s.

Then a dove exploded from my heart!

What had been a thorn tree where sparrows hid in fear of the hawk

became a simple heart again, white doves

flying out of it!

six

Sacrifice is not blood running down a cross of locust wood,

nor hands full of thorns.

It is looking at my own face in the river and seeing

your eyes, your smile.

I hear a voice whispering my secret name,

a voice made of Brazos water and a name made of light that falls blue as rain.

You tell me we have started digging a river and that the river will flow.

But however difficult it might be,

we must endure the bite of the pick, the shoveling out of everything

that is not bloody with love.

There is a fire that starts in the marrow and burns outward

through hands red as maple leaves.

There is a wound in all of us, red as a mouth that won’t stop crying,

not until its tongue is a tongue of fire.

When fears cease, this world shines like one drop of rain among a billion others.

The sky folds down across each drop like a Mother’s shawl.

seven

Let me tell you about the night I married Jesus.

It was in a cinder block church that smelled of mold, trapped gas and chewing gum.

It was the summer I turned fifteen and there was just enough breeze

to keep pastures from bursting into flames.

I put on white overalls and stepped with my Grandfather

into a galvanized tank of baptismal water.

While the congregation sang

“In the arms of my dear Savior O there are 10,000 charms.”,

I went down into water full of stars!

In that water Jesus lifted the bridal veil and showed me one glimpse

of my own face.

In that water he betrayed this world with his kiss.

When I returned to the one I pretend now to be,

answering to his name,

there was still the imprint of a place where we have no beginning.

Where there is not a single breath of air and no focused love,

only love delighting in itself alone.

If you are thirsty, kneel down in this water.

If you are covered in wounds, bleed into this fire.

If you are crying, let your tears be tears of joy!

.

DEATH IS COMING

.

When death reaches me there will be a marigold of fire brilliant as an eye

opening in the palm of my hand.

There will be a light rain of singing as I am carried down river in a boat of leaves.

When I die there will be one second of fear as when Carol reaches out at night

to lay her hand on the soft of my throat.

Fear will leave that quickly as when she rolls against me in our bed.

Even now I hear a voice like three creeks woven into one

with a skin of ice across it.

I see a circle of river rock with a fire burning inside it like an open

eye.

This is one kind of happiness.

..

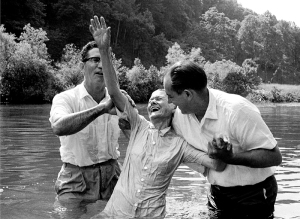

BAPTISM BY IMMERSION NEAR THE TRINITY RIVER

Grapeland, Texas 1959

It was November and she would not wait until Spring

so we drove to a farm close by the church and gathered round a cattle tank

to sing

“Shall we gather at the river…”

But the Trinity was treacherous and full of gar.

The Trinity was full of holes.

The preacher wore white overalls, the woman a gown made from a bed

sheet.

They stepped into shivering water like two blue herons.

I remember the smell of mud around the green tank

covered hard with hoof prints and cow patties,

the steers we boys had driven off with swords of willow.

It did not take long to hold a handkerchief over her nose and mouth

to let her three times down into the body of the Lord.

She went down shivering into ecstatic waters.

She went down shivering in ecstatic water.

.

CHARLIE REED

CM Reed, age 16

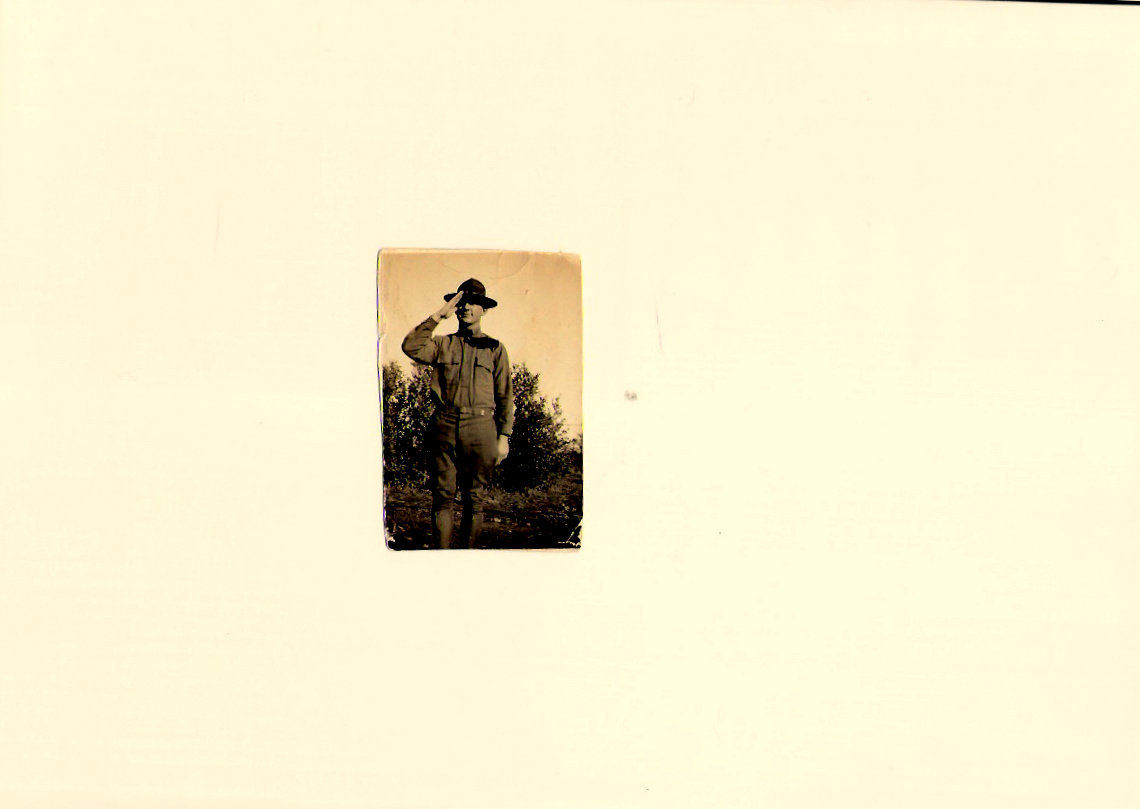

For My Grandfather, Charles Marion Reed, 1896-1987

1

“Charlie boy, the world is a painted woman.” CM Reed

His voice was birdsong.

His voice was verses torn from the Bible in a wind storm.

A quiet man living among women, keeping excess of joy

to himself,

always cheerful like a cool glass of sweet tea.

Simple as a breeze out of McLennan County where Waco, Texas squats by the Brazos

like a hound dog contemplating a headless squirrel.

Born out of ground plowed wide for cotton, out of hay fields

cut and stacked

where lonesome hawks hunkering on fence posts watch for mice

creeping in the stubble.

Land where prairie fever makes the people sweat with love for the Word of God

but not for the man himself.

Land famous for radio preachers, auctioneers

and cowboy yodelers.

Wanderers of the wasteland who sang like coon dogs with chicken bones

caught in their throats.

Five foot two, shoulders wide as a church house door,

high waisted, narrow prairie lips,

work hands that could tear thorn trees out by the root!

Little smiling eyes like a chickadee’s, alert as campfires

in the night.

Round head, dainty feet, nose you could stable a mule in.

His ears were large, wide opened as hand held fans,

the kind the mortuary gave to women of the church

depicting Jesus rising from the dead.

He could wiggle them like an elephant’s to please his grandsons

anytime we asked.

Owned the King James Version of the Bible recorded unabridged

by Efrem Zimbalist, Jr

but believed his own voice, pitched high as a wind in a chinaberry tree

and quivering like a red bird’s,

was sufficient to sing God’s name in the privacy of his bedroom

converted from a one car garage.

2

“Charles, a nigra should be listened to, same as you would a white man.” CM Reed

Unkind words were never intentional.

Seldom did they fall from his mouth without his notice,

warm and happy, like a little boy pissing on a hot rock.

After the First World War he taught in a one room school house

built upon a slight rise of ground outside Waco.

When he wouldn’t give passing marks to a white but undeserving share cropper’s son,

the boy and his father laid for him with twenty-two rifles,

firing up hill from a run off.

In a voice somewhere between a bluejay’s and a mockingbird’s,

he explained to me

how they could have lowered their sights a little and killed him

if they’d known that even in Waco, the world is round.

Favored by Jesus and cognizant of the curve of earth,

Charlie Reed lived

while their bullets flew high and fell exhausted and ashamed

into cotton fields.

During World War Two he moved to Huntsville with Nana

and Aunt B

where they all attended Sam Houston State Teachers College

while living in a quonset hut.

After class he chatted with German POWs held nearby,

telling them how God choose Texas as a fortress for His people,

quoting scripture to them through a bob wire fence.

1949 in Spring Branch, Texas, he taught high school science for a year

before they fired him.

He refused to teach the theory of evolution

and fought once in the class room with a disrespectful rough neck boy,

lapping blood from his face burned dark as sludge

on off shore derricks.

A boy whose hair was combed into simulated flames,

held high with butch wax in currents of oil!

It was easy for me to love a man so fond of himself,

so old and self content in his garden, hair the color of a halo.

When he was 80 and cut his thumb off in a wood chipper,

he and I buried it in a row of turnips.

Charlie Reed was a lantern swinging in the dark between the hay barn

and the Brazos,

always a light and a satisfaction to himself.

Never tiring of his own stories,

he spoke of himself as if he were a wealthy friend,

someone always ready to loan him money.

3

“I always got along well with Taurian women.” CM Reed

I remember his Mother, well under five feet tall,

voice like a locust scratching in a match box.

Lying in bed in her nineties smelling of talc,

she complained of leg pain,

the leg my Grandfather broke, running over her in a Model T Ford,

the first one in the county.

Her father had been scalped by Comanche Indians!

As long as she lived she saw them lurking in pin oak groves

and in the graveyard near Prairie Hill where an old Comanche man

converted to a Methodist

was buried outside the graveyard gate under a flowering oak.

A heavy rain came when they dug the hole to put him in.

When the ground dried,

it opened like a grandmother grinning at the sky with her teeth out.

Five feet down you could see his skull

long gray hair braided into a river of dust.

4

“Sixty-eight years of marriage and I never found a fault in her.” CM Reed

My Grandmother had skin more dusky than the average white woman.

Her nose was wide and turned up, with her nostrils flared.

“She could drown in a rain storm.” is what they said.

Seeing her picking cotton in the fields with a scarf around her head,

her neighbors would remark,

“She’s bound to have some Mexican in her.”

but they were thinking darker thoughts.

Nana’s hair was long as a sermon until she finally cut it.

Let down from braids at night and brushed out,

her hair was like the Brazos River curving round a hip bank.

After 1960 she kept it short and silver blue

as the barrels of a shotgun sawed eight inches from its stock.

Lying on her back in summer when she was a girl,

she was waiting for a breeze to part the curtains

and come inside her room to cool the sweat between her breasts.

Nana dreamed herself on a sandbar in the river.

Dreamed her whiteness slightly muddied by the water,

while the moon came upon her, looking in her eyes.

Nana came from rich farmers out of Lubbock.

Her father was famous for saying, “I smile like a jackass eating cactus.”

He foresaw the drying of the land and sold out after the war.

One sister married a banker from Lubbock with a John Deer dealership.

The man was as short and swelled up as the pecker of a boy,

who eats his fill of water melon just before he goes to bed

and wakes engorged, delighted with the world and with himself.

He smoked cigars big around as a newborn baby’s thigh.

Made his fortune at the bank, taking back the farms

of men with faces burned and rutted as the soil.

Families knocked to their knees with hands knotted in prayer

blown bankrupt out of Lubbock.

Lifted up as human dust and driven North of Texas by the wind,

they flew over mountains named for Jesus’ blood

where a remnant chosen by the Lord fell gracefully into irrigated rows,

come to rest in sugar beet fields of Southern Colorado,

where some of them prospered again and were saved.

5

“It wasn’t my fault your Grandma could never have a son.” CM Reed

Charlie Reed was not popular in Coldspring before the war.

He was farm agent for the county

and made enemies of white men, forcing them to pay in seed

what they owed black share croppers for the corn they grew.

Born in Central Texas he was considered almost a yankee!

Neighbors laughed when he broke his leg kicking a billy goat

in the head.

Bitten by a rabid squirrel, he had to go to Austin for the serum

that was shot into his liver

through a needle long as a seed bull’s pecker.

First time he entered the Coldspring courthouse

of San Jacinto County,

hogs were roaming in the foyer free as citizens!

Sows and their piglets tapping down the hallway

leading to his office!

As he told me this, his face was wide open as a sky

in which the half moon can be clearly seen in light of day.

His eyes were fierce as a child’s pretending to be angry.

Lying back in his easy chair with duct tape on the arms,

he told how he drove those hogs out like Jesus did the money changers,

past the pillars of the Court House into the muddy road!

Forty years after those days,

his voice pitched high as an oriole’s leaving the safety of a sycamore

to light upon the ground,

he told me about a gangster’s son he and Nana wanted to adopt.

But the gangster wrote a letter from Huntsville Prison

threatening to kill them if they did.

It was the same year Bonnie and Clyde traveled through Coldspring

leaving a note under a coffee cup that said,

“Next time we come, we’ll paint this town in blood.”

But Clyde was driving north and east that day

toward Bienville Parish, Louisiana

where the gang was shot so full of holes, the sky could be seen

streaming through them!

6

“Treat your Mother well and read a chapter of your Bible every day.” CM Reed

After Nana died of stroke, he held on for a year,

before a coiling breath of air found him sleeping in his easy chair.

He was watching re-runs on a buggy summer night

when a breeze came from the south through rusted window screens

and touched him gently on his forehead, as a wife would do.

Cicadas in mimosa trees were praying loudly and in tongues

about the fatted calf, the sacrificial lamb, the bride

and the bridegroom waiting at the altar.

But only Charlie Reed sleeping in his easy chair could interpret

these voices.

Nana and his Mother and a still born son without a name

were calling, “Charlie, Charlie Reed…”

And he was lifted up as tumbling ash above a prairie fire.

As husk after the harvest he was carried circling into air,

all his work finished, all his grain stored in silo towers.

Charlie Reed was lifted up, inhaled as dust and chaff into a breathing wind!

All that was left of him, every scrap of his being came together

in a spiral lifted high!

And taking on an angel’s shape composed of singing dust,

he left this place, he traveled and was gone.

CM Reed 1918

.

A MAN WILL ABANDON HIS FACE

There was a story my mother told me of a dust storm in Lubbock, Texas

before the war.

Cattle caught in a depression went sand blind

and the green was scoured from 4 door sedans.

But now I am nobody’s son.

I am not the boy who fell from the roof of a 3 story building and lived.

From where I lie in the dawn

I can see the moon like the horns of a bull and the last star of morning.

But I am not the one who ran with red colts in the field

who ran with calves kicking up their polished hooves.

I am not the bull with the moon caught in his horns.